An Inclusive Approach to Human Centered Design

Upon first hearing the term “Human Centered Design & Engineering,” several images may come to mind: scientists researching human subjects, artists drawing out schematics or maybe even engineers crunching numbers as they build a new product. Personally, I first imagined designers that work closely with engineers to create products that satisfy human needs. After asking around, I also gathered that human centered designers develop interface systems that bridge the gap between humans and technology.

As it happens, my initial perception of HCDE, while vague, was not altogether flawed. However, after taking the time to explore design principals and supplement my understanding with several academic sources, I have found that my working definition of the discipline has become largely altered. In response to these recent insights, the remainder of this paper will expand upon my current understanding of HCDE. More specifically, I will further define HCDE, discuss some relevant literature that supports my interpretation and explain how I have tied HCDE into my future career goals; namely enabling the disabled community through technology.

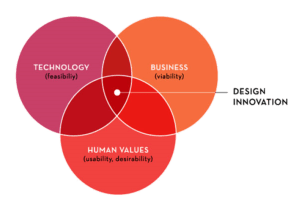

In general, I see Human Centered Design as an approach to product engineering that directly helps people utilize the benefits of technology. Yet, I feel that HCDE has much more to offer than can be stuffed into one concise sentence. First and foremost, I find it important to characterize HCDE as innovatively interdisciplinary. As can be seen in figure 1, designers must work to understand the perspectives of users, programmers and marketers so that they can integrate the needs and abilities of all parties into a functional, cohesive design.

In addition to enabling communication between fields, human-centered designers advocate for the perspectives of the general public, working under mantras such as “put users first.” As Jakob Nielson describes in his book Usability Engineering, designers enhance the user experience by addressing five measurable components of usability: learnability, efficiency, memorability, errors and satisfaction (Nielson, 1994, p. 26). In parallel, the meaning of these terms can be more readily understood through the following series of user-centered questions. Can users operate the device? Can they use the device to its full potential? Can they continue to use the device without regression? Can users recover if they operate the device incorrectly? And does the device elicit a positive emotional response from the user? Accordingly, human-centered designers conduct usability research or user experience research (UX) in order to determine if these criteria are met when humans interact with a technology. Essentially, it is seen that technology should not simply function; it should be utilized to satisfy human needs.

As a result of its extensive social focus, HCDE amounts to more than a set of static research, design, programming and management skills. It is also a way of seeing things. According to engineer Mike Cooley, product developers often mistake the design process as a linear track (Cooley, 2000, p. 64). Nonetheless, as Pinch and Bijker’s analysis of the Social Construction of Technology (SCOT) would support, understanding the successes and failures of products requires a multidirectional approach (Pinch & Bijker, p. 403). In this light, human-centered designers reject the idea that there is “one best way” to design products (Cooley, 2000, p. 64). Instead, they work to innovate, finding importance in cultural, educational and product diversity (Cooley, 2000, p. 65). Ultimately, it is this attention to human factors that enables designers to mold mere machines into usable tools (Cooley, 2000, p. 65).

Subsequently, I feel that the ability to connect man and machine has profound potential when it comes to helping people lead a higher quality of life. In their article “user-sensitive inclusive design,” Allan Newell and Peter Gregor emphasize that human-centered designers must place their products within a social context and consider all social groups including minorities (Newell & Gregor, 2000, p. 39). Outlying perspectives are often overlooked under conventional models, perhaps the most pertinent viewpoint being that of the disabled community (Newell & Gregor, 2000, p. 43). However, by identifying, understanding and reaching out to the vast spread of social groups surrounding technology, HCDE has the potential to extend a product’s range of usability to a wider demographic.

Opportunely, it is this inclusive and human-centric perspective that I intend to utilize in my future career. While I am eager to use science and technology to help people in general, familiarity with the needs of my blind older brother has made me adamant about designing products that satisfy the underrepresented disabled community. It is often overlooked or simply unrecognized that disabled users, for example blind users, have significantly different values and needs than the sighted. By the same token, while Donald Norman defines the concept of visibility as “the mapping between intended actions and actual operations,” many designers make the mistake of equating this idea with solely visual cues (Norman, 1998, p. 8). As is addressed in figure 2, when designing with the blind in mind, visuals like color and print are not useful. If users are to understand the function of an object, designers must integrate tactile indicators or audio feedback (McElligott & Leeuwen, 2004, p. 71).

Ultimately, if braille was integrated into more products the range of usability would dramatically increase. Products could be accessed by everyone from the sighted, to the elderly or vision impaired, to the blind. Likewise, enabling audio feedback or other non-visual user interfaces on computers and mobile devices would improve the usability of electronics; one of many approaches being outlined by Savidis and Stephanidis in their proposal for developing “dual-user interfaces” in computer systems (Savidis & Stephanidis, 1995, para. 2).

At this point in time, I am not entirely sure where such a specific focus will take me. I know that major technical corporations often support the UX research that I am interested in. Microsoft even does some work testing their software for compatibility with screen reading technology used by the vision impaired. Recently, I have also stumbled upon a group called Robots for Humanity, which designs and engineers mobile robotic systems to serve as surrogates and helpers for the disabled (Chen et al., 2012, p. 1). Although I think I would be quite content working in user research or user experience at a large scale company, innovative start-ups including Robots for Humanity seem to offer a more holistic experience and ultimately capture my attention.

In the end, I predict that, as long as I am able to take a human-centered approach, I will enjoy my future career whatever it may be. With its user-centric philosophy, I feel that HCDE will provide a suitable framework for achieving my technical as well as humanitarian goals. Moreover, as my working definition of HCDE continues to expand through experience, I am confident that I will find even more ways to connect its many principles to my future endeavors.

References

Braille-inspired design for the blind (n.d.). Pinterest. Retrieved November 17, 2013, from https://www.pinterest.com/pin/59532026296941333

Chen, T. L., Ciocarlie, M., Cousins, S., Grice, P., Hawkins, K., Hsiao, K., … & Takayama, L. (2012). Robots for Humanity: A Case Study in Assistive Mobile Manipulation. IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine Special Issues on Assistive Robotics, 8.

Cooley, M. (2000). Human-centered design. Information design, 59-81.

Information and design. (n.d.). dsin 2 n4m. Retrieved November 17, 2013, from http://n4mndsin.wordpress.com/2012/02/21/human-centered-design/

McElligott, J., & Van Leeuwen, L. (2004, June). Designing sound tools and toys for blind and visually impaired children. In Proceedings of the 2004 conference on Interaction design and children: building a community (pp. 65-72). ACM.

Newell, A. F., & Gregor, P. (2000, November). “User sensitive inclusive design”—in search of a new paradigm. In Proceedings on the 2000 conference on Universal Usability (pp. 39-44). ACM.

Nielsen, J. (1993). Usability engineering. Boston: Academic Press.

Norman, D. (1998). The Psychopathology of Everyday Things. The Design of Everyday Things (pp. 1-33). London: MIT.

Savidis, A., & Stephanidis, C. (1995, May). Developing dual user interfaces for integrating blind and sighted users: the HOMER UIMS. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 106-113). ACM Press/Addison-Wesley Publishing Co..

Pinch, T. J., & Bijker, W. E. (1984). The social construction of facts and artefacts: Or how the sociology of science and the sociology of technology might benefit each other. Social studies of science, 399-441.